"They want to be the F1 driver, squirting champagne ... they don’t want the work, the graft"

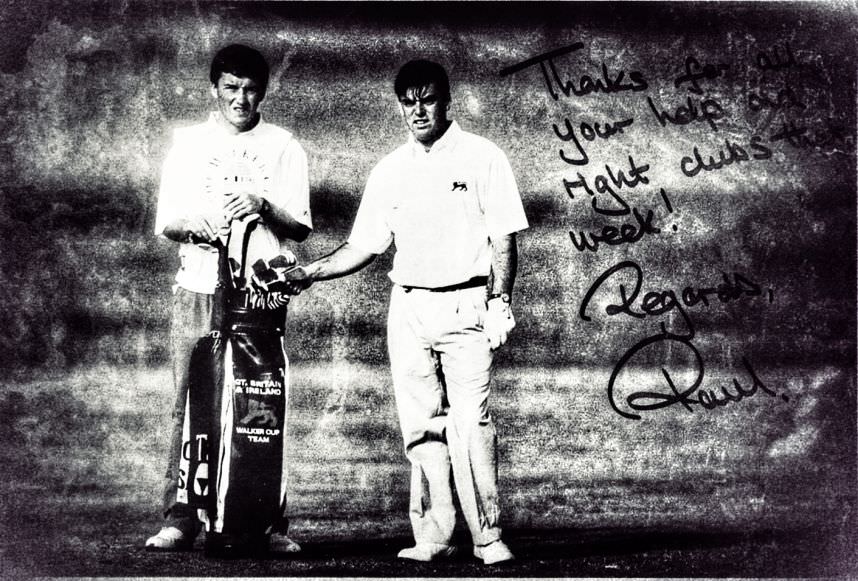

Damien McGrane (;eft) caddying for Paul McGinley in the 1991 Walker Cup at Portmarnock. "Thanks for your help and all the right clubs that week! Regards, Paul"

The Irish golfing universe is full of ambitious youngsters who’d give their right arms to play on tour but have zero interest in joining the P.G.A. But in one of the great ironies of golf, Damien McGrane, the European Tour veteran with close to €5 million in career earnings to his name, never wanted to be anything other than a P.G.A. professional.

The 43-year old from Kells in Co Meath grew up at Headfort Golf Club wondering if he could ever become as good a player as the club pro, Joey Purcell, who did it all from giving lessons and supporting the Irish Region to playing on the European Tour in the last 70s and early 80s.

Fast forward nearly 30 years and McGrane has a European Tour win to his name and strives for another on one of the most competitive professional tours in the world.

For all his down to earth ways, he’s an elite and highly competitive sportsman. And yet few things give him as much pleasure as the fact that he achieved his ambition and became a qualified, P.G.A. professional having served his apprenticeship under Purcell at Portmarnock Golf Club in the mid 1990s.

“I always wanted to be a P.G.A. professional,” he says with a passion. “But the young guys nowadays don’t have a desire to be a P.G.A. professional. They want the glitz and the big glamour. They want to be the Formula One driver, squirting champagne over everybody. They want that moment.

“They don’t want the work, the graft, the training, the teaching, the early mornings getting up at 6 am on Saturday and Sunday to open the pro’s shop in the summer time. They don’t want all that side of it. They want the glitz and the glamour. They do not want to be a P.G.A. member. But when I started out, my ambition was to be a P.G.A. member. That’s the difference.”

McGrane remains one of the Irish Region’s greatest supporters, regularly playing its Pro-ams and taking a keen interest in the welfare of his fellow PGA Pros.

“The sad reality is that guys now play golf for less than half the money I played for in the Irish Region years ago, so there is no desire among the young guys to become PGA pros,” he says. “When I wanted to be a P.G.A. pro, I wanted to be part of the whole package. These guys what to be part of the playing aspect only.

“At some point in a P.G.A. pro’s career, he is going to have to face reality. These people purely want to be players, which is great. I am a player full time myself, but I happen to be a member of the European Tour, so I can play golf and get well rewarded for it.

“But these other people don’t realise that it is difficult to be a player only and make ends meet because it’s a very difficult climate in Ireland and the UK at the moment. There is very little money to play for. So a lot of people at struggling and pros will struggle to pay his mortgage by playing only.”

No matter what happens to McGrane’s form, he knows he will always be a PGA pro.

“The day I am finished playing full time golf, I will go back in as a P.G.A. pro. The following day,” he says, adding with a chuckle. “At whatever club they are giving away the money for free.”

Having served is apprenticeship at Portmarnock and gone on to work as the club professional at Wexford for eight years from 1997, he has no qualms whatsoever about returning to that world when he hangs up his tour card.

“I have no fear of that,” he says. “That’s why most of us went into the industry — to interact with members and work at the parochial level. And because I have done my training, I will go back to that industry. People who haven’t done the training, don’t have that option.

“And training now is so extensive and so difficult that the young men and women now are super qualified and great credit to them. The problem now is that you cannot really make a living playing golf so you have to be capable of running the golf shop and training the members to be better golfers in order to make ends meet.”

Not all tour stars began as plus five handicap wonderkids, signed up by agents while still in the amateur ranks. For every Jordan Spieth or McIlroy out there, there’s an Ian Poulter or Eamonn Darcy folding Pringle sweaters.

McGrane is another member of that brotherhood who triumphed through sweat and tears and his career is especially interesting in that he was no boy wonder. He got his first handicap — ten — in 1986, when he was already 15 years old.

Within two years he was the No 1 player in Headfort’s winning Provincial Towns Cup team and by 1988 he was crowned Irish Boys champion at Birr, where he finished three strokes ahead of a promising youngster from Stackstown by the name of Pádraig Harrington.

Still there was no question of getting star-struck, even when he took Mark Gannon to the 20th in the quarterfinals of the Irish Close at Baltray in 1990.

The real star that year was a big lad from Dungannon with streaks in his hair and a game to match — Darren Clarke — who went on to beat young Harrington 3 and 2 in the final.

While Clarke went on to turn professional the next year, joining Chubby Chandler, and Harrington became a three-time Walker Cup player and an accountant before eventually turning professional five years later, McGrane did things his way.

He was never going to be a flashy ball-striker in the Clarke mould or even a Harrington, so in 1991, having won an Irish international cap against Scotland at Youths level and captured the Kilkenny Scratch Cup and the Connacht Youths title, he became an assistant to Purcell at Portmarnock, caddying for Paul McGinley in the Walker Cup that year.

There was to be no European Tour Qualifying School adventure for McGrane for another five years. His mission was to learn his trade, build up his confidence and see how good he could become. As it turned out, he was very good, as Harrington recalls.

“I’ve known Damien a long time and I would always have put him down as a really strong competitor,” Harrington says. “He is probably the best role model out there for any pro going on tour. He is somebody that everyone can learn from.

“There are very few people who understand themselves as well as he does and have a better approach to what they do.”

Peerless as a grinder and a competitor, he established himself on tour through the PGA route, turning professional under Purcell in 1992, winning the Irish Assistants Championship in 1993 and 1994 before moving first to home and Headfort and eventually to Wexford.

He remained there as club professional for eight years, combining forays onto the EuroPro and Challenge Tours with his PGA Irish Region career before finally breaking into the big time.

His story is not exactly a conservative one — he took his own chances and put his own livelihood at risk. But it is a story of perseverance and discipline.

As Purcell recalls: “The fellas on the tour would have given their right arm to have the short game Damien had, even at age 17 and 18. Once you have that and you bring a half decent long game to it, it’s amazing what you can do.

“He was basically trying to get his qualifications as a club professional and work from there. He simply set his goals. I think he repeated his leaving, decided he wanted to become a club professional and qualified as that. Then he realised, as his game got better, that he might make it.

“Like everyone else, and I was no different, he had ambitions but times have changed and Damien deserves enormous credit for making it.”

It’s attitude more than aptitude in McGrane’s case.

“I always saw him as a dogged guy who never gives in,” Harrington says. “But he is far more than that. Way, way, past that.

“He fully understands what he is doing and he is a very experienced pro who fully recognises how to get the best performance out of himself. And this is where the credit lies, he would be ahead of 99 out of 100 pros in that department. You would struggle to find 100 pros who are as comfortable as he is.”

Career winnings of €4.8m do little justice to McGrane, the patron saint not just of Irish PGA pros, but those who root for the little guy in a big, bad world.

“It’s difficult and standards are extremely high and it’s a very, very closed shop,” he says of life on tour and the challenge facing the younger players trying to make that breakthrough. “The one thing you have to have is the desire. And if you have desire, you will build up and get on that tour.

“Quite off the confidence of a top amateur will take a kicking. All of a sudden, they are bottom of the ladder and if things go wrong, their confidence can be devastated. When Shane Lowry won the Irish Open he was thrown in a the deep end and his first year must have been extremely difficult.

He was probably lucky to survive. But he’s gone from strength to strength because of his attitude.”

Looking at young players stuck on the mini tour grind for year after year is something that McGrane cannot fathom, especially when he sees those players looking for sponsorship money.

“If I was one of those lads and I missed out at School I’d be straight back to my club job until the school the next year. Now these guys are watching MTV until it is time to go back because they are in no man’s land.

“They don’t want to be the guy giving 10 lessons a day, the P.G.A. pro who is working. Some turn around and say find me somebody to give me money for free. Whereas a P.G.A. pro can work for his money and reinvest it in his golf game. Some people you are talking about only want to the money for free.

“They want €10,000 to play and want somebody to give it to them. They don’t want to stand on a driving range.

“I won’t say I didn’t need sponsorship. But I had no problem going home to Wexford, working for a week and whatever profit I made, the following week going off and playing the Challenge Tour. That system worked well for me.”

Golf has always been a numbers game and McGrane is aware that he has to maintain a high level or face extinction.

“Golf is a very simple game but unfortunately, it is very easy to get distracted and all of a sudden you have disappeared into oblivion,” he says.

With players like Thornton, Kevin Phelan, Gareth Maybin and Peter Lawrie all losing full playing rights last year, McGrane is well aware that nothing is guaranteed.

“If you can keep it simple, keep it basic and just let the golf do the talking, that’s the way forward,” he says. “Some guys get a little bit confused and start making it a little more complicated that it possibly should be and after two years you realise the guy has disappeared off the planet because of basic mistakes.”

The Co Meath man is conscious that with prize funds shrinking and competition for places now hotter than ever, he’s enjoyed some golden years.

“The economy was good, money was good and possibly easy,” he admits.

But he also knows that in many ways, it’s easier for a young player to feel that a career on tour is more attainable with greater access not just to European Tour players but also to coaching and mini tour competition.

“When I was a young man, I met Harry Bradshaw on a school golf trip when i was 15 years of age and I met Christy O’Connor Snr once. But you would never see a tour player. These days the European tour has made itself more accessible to people and guys can stand a few metres away from a European Tour player at the back of a driving range.

“I knew very little about golf and what really goes on. I had to learn by trial and error by myself. Whereas now with Youtube and social media, everybody knows a European Tour player and possibly has his phone number. Things have improved dramatically.

There are probably 20 young men who are trying to play on the Europro Tour whereas back in the day where were four guys - me, Gary Murphy, Peter Lawrie and David Higgins. Now it is a lot more accessible and guys talk about it now.

“I had a real job and I was self sufficient. I made my own living and I played those mini tours to move forward. Most of them now wait for somebody to give them the big blank cheque, which might have happened when the economy was good but it is not realistic any more.

“When I started in 1985, Joey Purcell was the only professional golfer I knew. I didn’t know what a professional golfer was. He could play golf better than I could and was able to play shots and I could watch him playing shots.

“He could describe and show me how he was playing certain shots . And that attracted me to the professional side of golf. And then obviously I had a desire to be as good as I could be. That was my introduction.

“Once Joey started playing the Irish circuit, I caddied for him. And if he shot one under par, he probably finished first, second or third that particular day. And I thought to myself, I could do that.

“Of course, I couldn’t. But I knew that if I got the rub of the green and a good bounce here and a good bounce there, that i could do that and that drove me forward to improve.”

McGrane didn’t plan to be where he is today but simply progressed from one stage to the next until he found himself on tour.

“I didn’t have a master plan to start on the European Tour at 30 years of age,” he says.

With his 44th birthday due to fall on April 13, he’s still got high hopes that he can win again having captured the Volvo China Open in 2008.

“There are a lot of good players now,” he says. “Within a month of getting on the tour, there are players out there now who can win a tournament. It just shows you how well they are prepared, both physically and mentally.”

The ultimate grinder, he continues to bide his time, waiting for that second win.

“I am hoping to get lucky and sneak a win here or there,” he says. “My age is against me but I am still there.”

He might be rubbing shoulder with superstars and playing for millions of euro but he’s still a humble PGA pro, and a proud one too.